12 Questions for Sean Thor Conroe

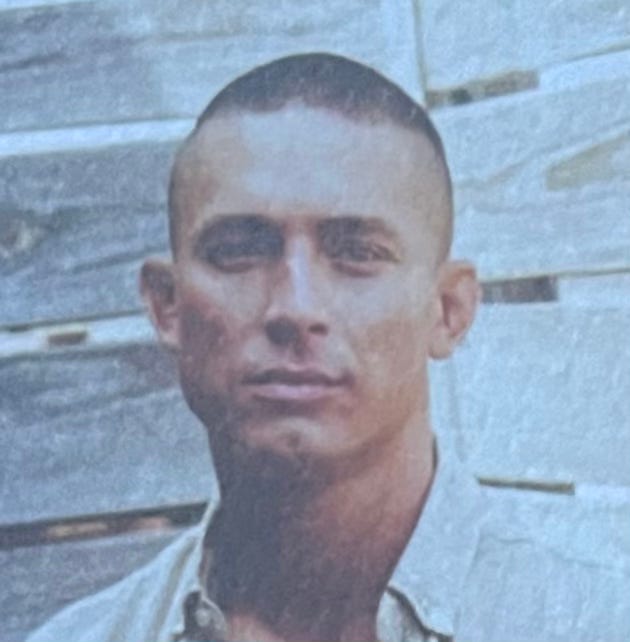

The 21st century's enfant terrible of the literary world on purpose, fate, destiny, progressive ideals, nicotine, and more.

We were talking outside of Dean Kissick’s new space on Orchard St about movies and books and writing and scenes and the idea of getting away, removing one’s self so the writer could finally begin to focus on what matters, how the writer is always trying to finally begin and focus on what matters, but then when we’re far away, away from the scene, from the world of industry and media that allows writers to live and to eventually be read, we become so caught up in our own minds and myopic conceptions of reality, too deep in the aesthetic, if you will, and then we decide we must go back, back to the events with the scenesters and gallerists and writer types, but not really writers, all the editor types, but not really editors, people who mingle and flirt but don’t know how to edit or even what STET means, and then there’s all the publishing types and art-lit-media world whores and fourth-rate fame-fuckers who’ve read nothing new since Patti Smith in college and Sally Rooney perhaps when their grandfather died, or boyfriend or girlfriend disappeared with someone younger and more attractive. And that’s literature to them, and this is who we’re spending all our precious time around, our one chance at life, and then the cycle would persist; we’d go on and get away. Sean begins to mention ‘how hard’ I’d been going on my new interview series, how he admires when a writer really goes ‘in on something.’ ‘Thanks,’ I reply. ‘But man,’ he adds, ‘it’s bout time for you to drop. You gott’a drop, bro! Drop a book. It’s time, let’s go. How old are you?’ ‘About to turn thirty.’ ‘Wow. Drop time.’ He started to list several books that’d motivate me to get going, to finally drop.

Of course in this conversation with Sean, the language of the literary world and literary events began to coalesce, sans-effort, with the lexicon of streetwear, of a variety of baggy-legged brands like BAPE and Supreme, one could even say distinct brands like Conroe himself. But this brand of high and low, as Sean says, is merely part of his art, something innate he can’t control: ‘In my personal view there’s no great divide, the divide is actually a cultural imposition. I don’t agree with the assessment that Fuccboi is made up of some kooky slang that has nothing to do with my world. It straddles lines in my language and different parts have different flows. I think that every book should be representative of what it’s about. For example, I’m writing a new book that has a different rhythm and flow than Fuccboi. But the thing is, like, the tone is consistent, I just use different tools depending on the narrative’s aesthetic. At the end of the day, my voice is just my voice. And with whatever project I’m on I go full-speed, full-speed ahead.’

*

Off a suggestion from Sean, I’ve spent the last few weeks reading one of Philip Roth’s nonfictions, Patrimony, about the sudden illness and eventual death of Roth’s father.